GLoG: Class Consciousness

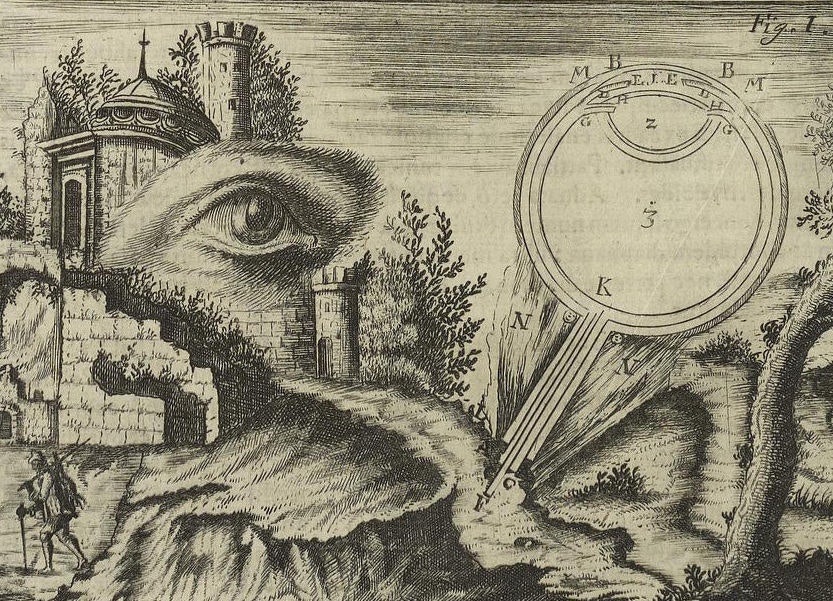

Image: Johann Zahn, plate from Oculus Artificialis Teledioptricus Sive Telescopium, 1658. Public domain source.

Image: Johann Zahn, plate from Oculus Artificialis Teledioptricus Sive Telescopium, 1658. Public domain source.

In my last post, I alluded to my belief (by way of games like Apocalypse World) that a character's class does more than furnish them with gear and abilities - it flags what kind of story a player wants to tell. We can speak in broad generalizations about genre or the class trinary of fighter, wizard, and thief, but here I want to address this topic in detail, describing the way GLoG classes are written and presented as a way of examining what GLoGs care about. I also hope this post is legible to someone new to GLoG, who might stumble upon some of my class posts and not have the context of steeping in hundreds of blogposts and forum discussions.

Describing GLoG through it's classes is a bit like trying to describe all cakes by reverse engineering one slice of red velvet. You can't just put the cake in the un-oven and then un-mix the ingredients to see what it's made of, nor can you deduce much about all cakes from the features of the individual, but we can closely examine the structural and material features of our slice of cake to speculate on what goals it was trying to achieve.

This text assume you'll pull up your favorite GLoG class (or one of mine, if you prefer) as a reference and practical example.

Name

Most classes have one. This feels like it's as much a function of blogpost titling as it is of distinguishing classes from one another. There are dozens of "Fighters" and hundreds of "[School Name] Wizards." Efforts to create central registries just don't keep up, so expect to keep the blogpost your character depends on at hand while playing.

Description

Usually only one to a few paragraph. Sometimes fiction, sometimes design notes. In either case, this is the elevator pitch. "Play this class if this sounds fun to you." I find that the most useful descriptions provide some sense of the world around a class - the institutions that they interact with, how laypeople think of them, what hooks a GM might have on them.

Starting Equipment

Here we come to the first concrete rules text and first real hints at what GLoG cares about. First, they indicate a dependency on another rules document. The combat statistics for a sword are usually not provided, nor are the rules for swinging one. This is critical for GLoG's modularity, allowing most classes to function in most folks' individual hacks.

Second, they indicate the poverty of GLoG characters. New characters frequently only have a handful of items. They rarely have gold or property and if they do it's often directly tied to the conceit of the class. For some players, this can be an easy narrative hook- "I became an adventurer because otherwise I don't know how I'm going to buy dinner." Personally, I am a bit leery of cosplaying poverty like this and prefer characters that adventure because of their beliefs or relationships, but the hunt for gold is deeply woven into many GLoGhacks.

Third, equipment is often combat focused. A class that doesn't start with some kind of weapon stands out as a novelty. Traditionally, fighter archetypes are partially buoyed by their access to a shield and armor. Much is often made of combat as a fail case of old school style play, but it's telling that so much of what a character does directly references it.

Finally, fixed starting equipment points to the short lifecycle of a GLoG character. If your character is particularly likely to fall into a pit of spikes, be gobbled up by an ooze, or turn themselves into a mass of writhing tentacles, you need a quick system for churning out a new character. Fixed starting equipment avoids the problem of needing to do arithmetic mid-session as you look up the price of a halberd for the dozenth time.

Starting Skill (Sometimes "Background")

Usually only a single word or short phrase, the skill represents what a character did before becoming an adventurer. It usually provides a concrete mechanical bonus (rerolls, modifiers, etc), but it also shapes narration. The GM may describe the way a wall is built in more detail because a former bricklayer is in the party. I think this has an outsized impact on the fictional world as it develops at the table.

Many classes provide several skills in a table to roll on. These not only provide options for differentiating multiple characters of the same class, but also create a sort of tableau. We can imagine the world in which a fighter is equally likely to be a bandit, a deserter, or a member of the nobility and we read into the relationship between the three terms.

I think skills are loadbearing, even if they often don't get specifically invoked at the table. If a class doesn't have a skill at my table, I insist that a player invent one. It can't be the name of their class.

Templates

Almost always four, labeled A - D. Templates are acquired in succession as a character gains experience levels. They sometimes confer bonuses to attributes or other parts of the character sheet, but usually they provide Features (more on that shortly). It is a rare class indeed that provides a template that give no features.

Again, we encounter the short lifespan of the GLoG character. Templates are frequently front-loaded with many small features and core class defining features at the front and a big, showstopper feature at the front. Templates B and C sometimes feel a little muddled, like half-steps between those two clearly defined points.

This is a narrative arc of sorts. The character gets more experienced and gains prowess, deepens their connection to the archetypal thing that they are becoming. They gain one final, transcendental ability then typically retire if they live to see level five. Some authors, like Hilander, are doing some interesting work complicating this narrative arc by tying the features to actual story beats and not just the gradual experience of power increasing.

The template system also contains the promise of multiclassing. There is a whole other blogpost to be written about whether this promise is actually realized, but in theory a character could be a Fighter B / Wizard B. For me, this points to two specific modes of play. One is the fantasy of being the jack-of-all-trades with a foot in multiple worlds. Someone not on the archetypal map. The other is that this appeals to a gamer who likes the puzzle of optimizing a character or finding the unexpected synergies between different systems. Ideally, this would apply a pressure for GLoG classes to provide their features with the most chance of being useful to a multiclass character first, but in practice I find that there is a lot of redundancy and a lot of features that are quietly incompatible with one another.

Features

The lion's share of the wordcount of any class is nested in features. These are verbs that a character can enact in the fiction and, interestingly, are typically the rules that the player is most responsible for adjudicating.

I often borrow my feature templating from Powered by the Apocalypse games and think many features boil down to this schema:

When X happens in the fiction, perform Y procedure.

The savvy player not only listens for the situations that make their class features relevant; they actively steer the scene towards scenarios that make use of them. A character who can translate any text by touching it is going to touch substantially more text than the average character. This is the principle action by which class shapes the fiction at the table.

It's worth making special mention of spellcasting as a special case of features. Due at least partially to a particularly elegant and persuasive resource system, spells are one of the primary creative outputs of GLoG authors. Spells break the above schema in that they don't require a precondition beyond the caster simply choosing to cast them - the power to make the scene different. This feels like a specific fantasy to me, and one that is evidently persuasive enough that many players are willing to forego almost any amount of concrete mechanical advantage or even the longterm survival of their character. GLoG is haunted by the shadow of the "linear fighter versus quadratic wizard" phenomenon of 3rd edition D&D fame, so many classes that can cast spells don't get much else. In practice, I find it's not often a major concern.

Many class features and particularly spells make use of a resource mechanic - Magic Dice, [Noun] Points, or even just uses per day based on level or the number of templates a character has acquired. At their best, these mechanics reward a single class character for investing heavily, allowing features to scale as the health and danger of their foes do. At their worst, these are a major sticking point for multiclassing and feel particularly likely to be ill-balanced, causing character classes to under- or overperform one another through sheer numerical force.

A Class Act

After all that, I don't know that there are many conclusions to draw here. I've painted a picture of a GLoG that is concerned with short-lived, combat centric, archetypal characters. This account underplays the roll that purchased gear provides in play at the table or the influence that systems of advancement express on player actions. I also think it points to a certain focus on the individual - GLoG characters are frequently about themselves becoming more of what they are. That is perhaps in opposition to a fiction that frequently wants to change them.

I'd be interested to hear your thoughts. Are there facets of classes that I have missed? Notable exceptions or subjects I've misconstrued? There isn't a comment section on this blog, but reach out to me and I'd be happy to write a "Letters to the Editor" post sometime soon.