Is Your RPG Book Art?

Unambiguously yes, but that bar is too low.

Recently, Markus over at Personable Thoughts wrote:

I think we should therefore also consider the RPG book's role as an art object, separate from its gameable context or use as pseudo-fiction.

This comments comes on the tail of a conversation thread on Discord (and perhaps some other ripples I've seen on Bluesky?). My response? I agree, absolutely, but I don't think most games can take that heat.

I have no particular authority to answer this question. I make and teach art making, but you'll find as many opinions on what counts as art as their are artists and many of those have their thumb pressed closer to the post than me.

Let's start with some definitional work.

"What is Art?"

From my perspective, asking "what is art" is both a central thread of contemporary art discourse and a question that breaks shibboleth. Much has been written about Marcel Duchamp's Fountain - a urinal signed, dated, and rejected from display in a gallery show. Duchamp describes this work (and works like it) as "everyday objects raised to the dignity of art by the artist's act of choice."1 The popular critical interpretation as expressed by the Tate is that the work "invites us to question what makes an object art?"2 Is it the gallery presentation? The signature? Being photographed by a semi-famous artist? The material connection to ceramic or marble?

Marcel Duchamp. Fountain. 1917. Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz against a painting by Marsden Hartley. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The "act of choice" (or artistic intent as it is sometimes called) has been a popular means of authorizing artworks in the intervening century. Whole movements have sprung up and withered away that take working with garbage or only manipulating materials found at a physical site as their core premise.

This is, of course, only half the story. Artists can call their work art until they are blue in the face, but that only matters if their audience believes them. We might construct any number of pretenses to support that claim. Again, gallery presentation, signature, photographs shared by a recognized artist, etc.

In my experience (again, one among many), in conversations with fellow artists we short circuit this conversation. We take the corollary of the "act of choice" and say "if we are talking about this as a work of art then it's a work of art." This is a foundational mark of respect that lets us present work to our peers that might be provisional or vulnerable and still get feedback or engage in conversation. If a stranger came into one of those conversations and said that an object we were discussing was not art, this would be taken as either a) a comment made by someone unaware of all the traditions referenced above, perhaps to be taken with a grain of salt, b) a damning insult, effectively saying that the work was so bad as to be beneath serious consideration, or c) a social slight or signal of baked-in prejudice. Not recognizing something as art is a principle site of gate-keeping, a moment where folks' -isms run rampant.

How is the art?

All this is a long winded preamble to say that calling an RPG book an art object in italics does not necessarily convey the a priori depth of meaning that it sometimes is taken to denote. It merely suggests that we are going to consider it using a certain set of tools.

(To be clear, I don't think Markus is hefting the term as a valorizing cudgel. I think they want to engage in this kind of close reading, particularly with an attention to beauty and how it is deployed)

But what tools? We could assess RPG books from all sorts of angles. Thomas McEvilley provides a helpful, inexhaustive list in "Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird":

- Content that arises from the aspect of the artwork that is understood as representational.

- Content arising from verbal supplements supplied by the artist.

- Content arising from the genre or medium of the artwork.

- Content arising from the material of which the artwork is made.

- Content arising from the scale of the artwork.

- Content arising from the temporal duration of the artwork.

- Content arising from the context of the work.

- Content arising from the work's relationship with art history.

- Content that accrues to the work as it progressively reveals its destiny through persisting in time.

- Content arising from participation in a specific iconographic tradition.

- Content arising directly from the formal properties of the work.

- Content arising from attitudinal gestures (wit, irony, parody, and so on) that may appear as qualifiers of any of the categories already mentioned.

- Content rooted in biological or physiological responses, or in cognitive awareness of them.

"Content" here refers to basically anything that we might describe about an artwork. The act of description is the act of interpretation. I think it's also a valid point for assessment. How much does a given work have to say on each or any of these axes?

Select an RPG book from your shelf. Flip through it. Try weighing it on each of these axes. What kinds of content do you find? How has the author manipulated the book (the actual object) to communicate that content? Some of them may not apply. That's totally fine! Still, I think its reasonably standard that an artwork should communicate articulately through its form in at least a few of these categories.

Note that I am not separating form from the text as it functions. I don't think that's a luxury we have if we are considering books as art objects. The words on the page ring out in unison with the font choices, the binding, or the illustrations. Or at least they follow shortly behind.

This is also a pretty low bar.

Some Artist's Books

Let's look at some non-RPG artist's books. These aren't canonical or anything; they are just some works that I like that might provide useful comparison. I've organized them roughly chronologically.

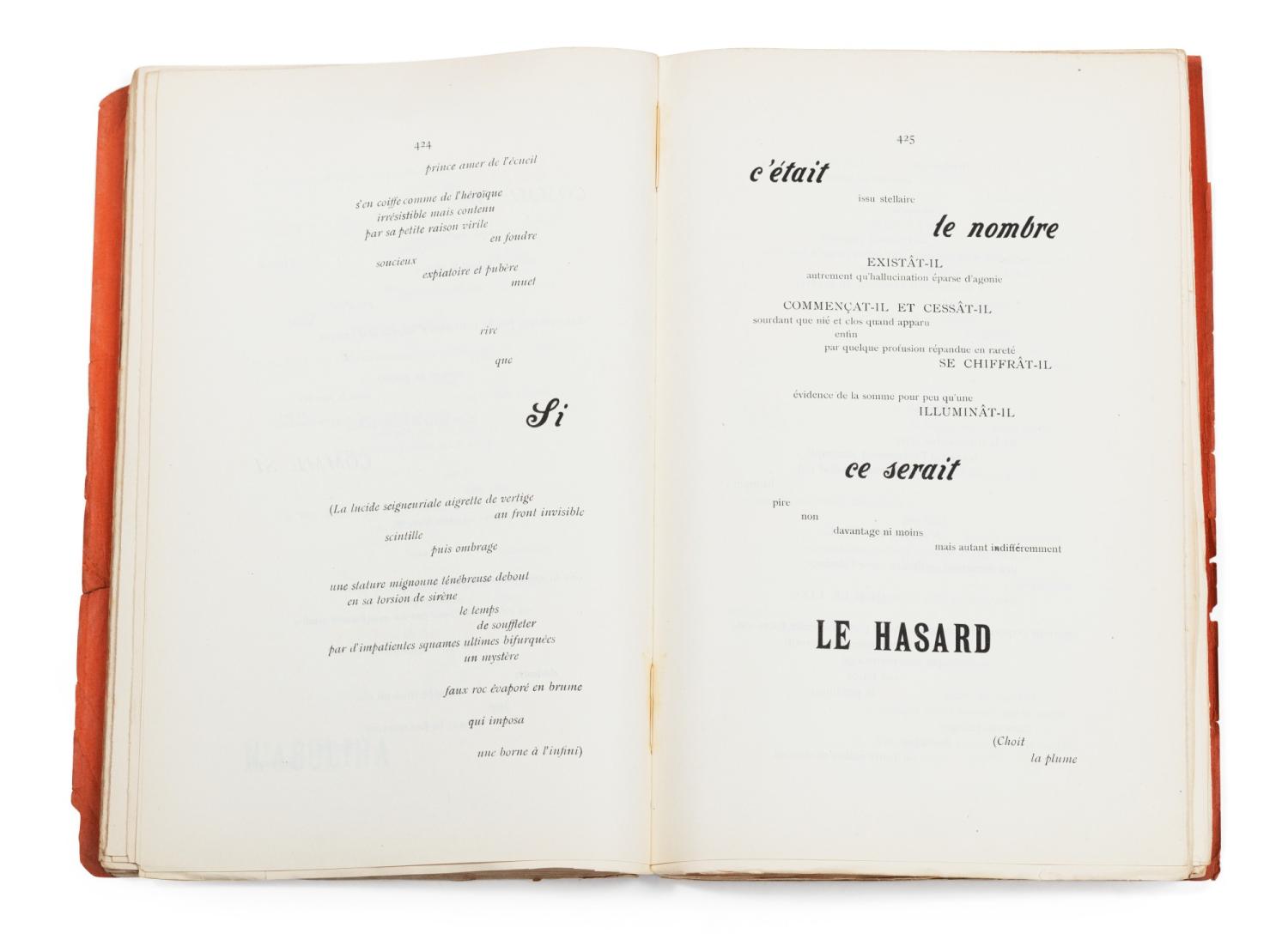

Stéphane Mallarmé. Un coup de dés jamais n'abolira le hasard, in Revue Internationale, 1897. via Michalis Pichler.

A Throw of the Dice WIll Never Abolish Chance

Ach! Immediately a single poem and not a book! Mallarmé's A Throw of the Dice Will Never Abolish Chance is an early example of concrete poetry. The flow of the text down the page not only mimics but performs the action Mallarmé describes, including the surprise (and sometimes dismay!) of the final result. Marcel Broodthaers published a 1969 edition that redacts all of the text, leaving only the music of visual weight and pagination with the goal of emphasizing how tightly Mallarmé controls this aspect of the work.

For me, this work directly connects to Tim Hutchings (Thousand Year Old Vampire)'s project: Homage to the Player's Handbook. Hutchings renders the AD&D PHB in grayscale, reducing blocks of text to wash-y rectangles of ink. The form of the text carries the work and speaks to its conceptual ends. We could (and many have) read into why TSR constructed these books the way they did.

Ed Ruscha. Twenty Six Gasoline Stations. 1962. Via Wikimedia Commons

Twenty Six Gasoline Stations

Of course, it would be reckless not to acknowledge that the commercial systems books are published in inform the way they are produced. Markus leverages this in their original post comparing luxurious hardbacks to more DIY zines. This too is a choice and space for artistic intervention.

Take for example, Ed Ruscha's Twenty Six Gasoline Stations. Like it says on the tin, the book contains images of 26 gas stations along the highway between LA and Oklahoma City. The images are black and white, printed in offset as cheaply as possible. The book was initially distributed in 1962 as stacks of copies dumped in those gas stations, designed to blend (or, perhaps, infiltrate) the cheap magazines we expect to see in these spaces. In the words of the artist, "all it is is a device to disarm somebody with my particular message"3

We might borrow a term from Cildo Miereles, known for works like Insertion into Ideological Circuits: Coca-Cola Project, Coke bottles engraved with anti-imperialist slogans only visible when full, then released back into circulation at a recycling drop-off. Miereles refers to these systems as "circuits" - both the systems of purchasing and recycling Coke bottles and the systems by which the United States exerts influence on his home country, Brazil. What are the circuits of contemporary TTRPG production? How do our book objects respond to, leverage, or disrupt that circuitry?

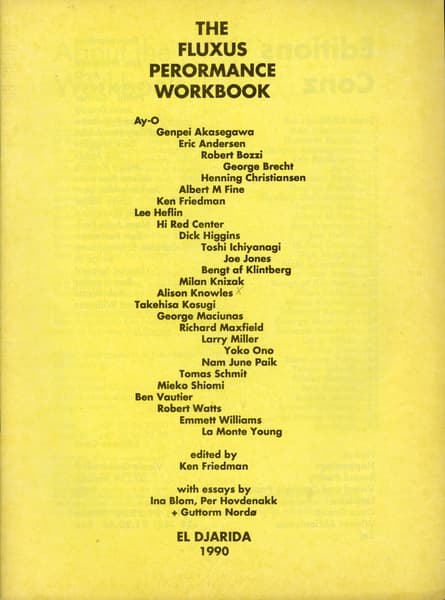

Various Artists. The Fluxus Performance Workbook. 1990. Via Edcat.

The Fluxus Performance Workbook

Another snaking pagination! The Fluxus Performance Workbook is a collected anthology of prompts for conceptual, often absurd performances collated from a who's-who of artists active from the 60s to today. For example, one of my favorite prompts is by George Brecht:

Three Lamp Events

on. off.

lamp

off. on.

In many ways, this book is quite close to an RPG rulebook. It contains a series of procedures. It takes for granted that the reader will be conversant enough in the genre it resides in to parse what is going on. The pieces mostly could be performed but some can't. As with RPGs, I think there is an understanding that many readers will simply read the prompts and only a handful will go on to actually perform them.

I think The Fluxus Performance Workbook presents an interesting counter-example to my line of inquiry so far. In terms of presentation it is quite plain and matter-of-fact. Someone made the book and laid out its various editions, but it is much more content to reside in the formal language of a conventional paperback or a pamphlet or whatever form is at hand. I think there is something to be said for a conceptually dense and often difficult to parse work opting for convenient formal means. If you know you are asking a lot of the reader, perhaps it pays to keep the form of the book from interfering. Or perhaps, as the prompt format suggests, the words are just auxiliary thrusters. They carry the work forward, but then detach when performed.

These are examples of higher bars, but I think we could ask RPG books to set themselves a goal along these lines.

Something Practical

I am wary of providing prescriptive advice on how to make a book better art. There are countless ways to do so and what works for you might not work for or even be legible to me.

What I can offer is a framework that I introduce to my students when they are called to write an artist statement. It was introduced to me by Lydia Moyer, one of my undergraduate advisors.

As you develop your manuscript consider the following:

- What is the form of your book? Literally, what is it made out of? How heavy is it? What typefaces did you choose and how is it illustrated?

- What is the concept of your book? What is it about? What references are you pulling from? What is your killer procedural or mechanical twist?

- What is the surprising revelation found at the intersection of your form and your concept? How does the concept articulate the form? How does the form impact the concept?

This is a dialectal approach. The form and concept are thesis and antithesis. They collide together and form a new synthetic object. The moon collides with a big ball of rock and suddenly we have Earth.

If you can't think of an answer to that third question, I think it is worth seriously re-evaluating your answers to the first and second. I think many, many RPG books fail this test.

This is a high bar. I try to hold myself to it, but it's worth remembering to just release your damn artwork and revise later as 200-Proof Games aptly reminds us.

Burst Like a Star

I hope by my meandering tone and frequent caveats I've indicated that this is by no means a canonical (or even thorough) treatment of the subject. I don't have access to the secret fire of good art. If you find any of my points contentious or even disagreeable, good! That's likely also useful information for navigating the complex topography of all possible artworks. Please do get in touch though.

I do want to briefly mention one final bar. In Rainer Maria Rilke's Archaic Torso of Apollo, the poet describes a headless Greco-Roman statue. Rumor has it he wrote this poem on the advice of his employer, the sculptor Auguste Rodin, who told him "go to the zoo and look, go to the Louvre, choose something, and talk about it."4

I'd suggest reading the whole poem. It's short.

Rilke concludes:

...for here there is no place

that [the statue] does not see you. You must change your life.

This is the highest bar. I believe firmly in the capacity of art to change your life. That means, I think RPG books can too. I don't know how to make art that does so.

If you find out, let me know.

Footnotes

- Martin, Tim (1999). Essential Surrealists. Bath: Dempsey Parr. p. 42.

- https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/duchamp-fountain-t07573

- Willoughby Sharp, ‘“… a kind of a Huh?”, An Interview with Edward Ruscha’, Avalanche, no.7, Winter/ Spring 1973, p.30.

- https://poets.org/text/archaic-torso-apollo